The Ways of Water

A complex water system is constantly at work year-round in the Sawtooth Mountains.

The ebb and flow of droughts, large snowpacks, and how they affect what is happening below the ground, profoundly impact the SNRA ecosystem.

For those not well-versed in the terminology surrounding water supply, the Sawtooth Society would like to provide a summary explaining the process from snowfall to a full water table. An important, and critically orchestrated exchange occurring in the SNRA throughout the seasons.

Above Ground

Snowfall in the Sawtooth Mountains

As the snow accumulates in the Sawtooth Mountains during the winter, streamflow is produced when the snow melts during spring and early summer. This run-off provides us with the necessary water to replenish the SNRA lakes and forests.

During any given year factors fluctuate- including changes in air temperature, precipitation, the amount of water being used by vegetation, and the preexisting water in the soil. Each year before the first storm arrives, the ground has already determined the amount it will be able to absorb in the upcoming season. This equates to the amount of runoff in the spring.

Ground Level

Snowpack in the Sawtooth Mountains

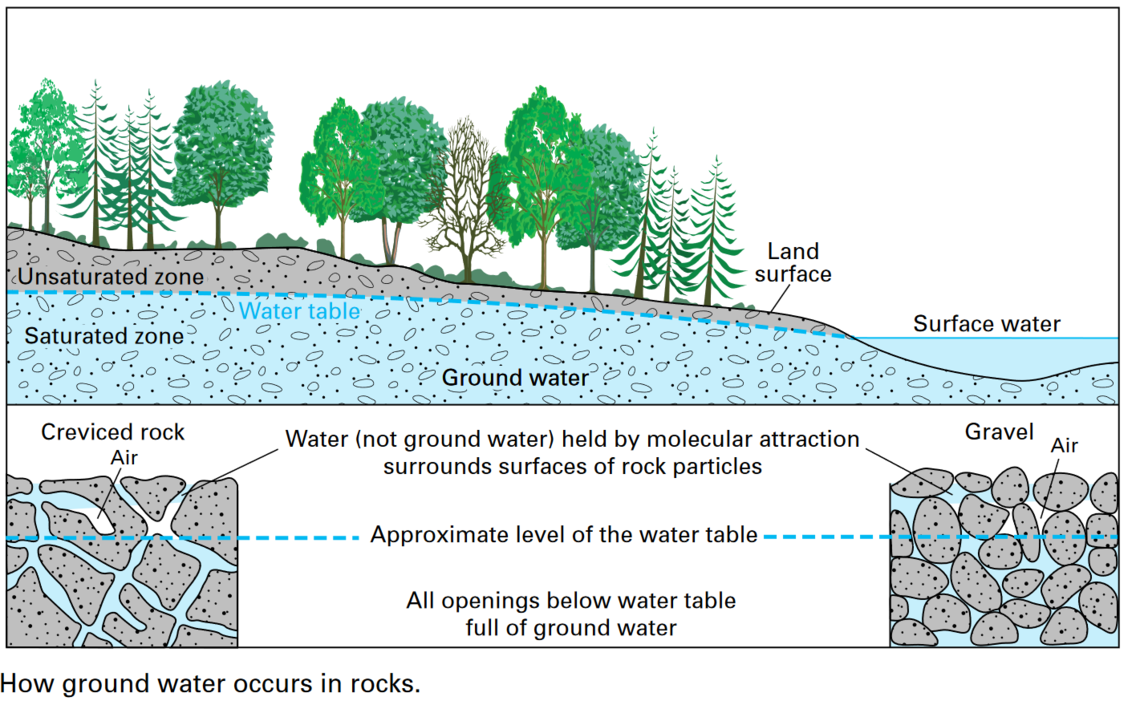

The unsaturated zone or zone of aeration is where the pore spaces of the rock or soil are partly filled with water and air. Just as a dry thirsty sponge can readily absorb spilled water, so too does dry, parched soil. It will easily soak up the melting water – more so than ground that is saturated. It also depends on the type of soil. Sandy soils will absorb more easily whereas clay soils will require a bit more time to soak in. This process is known as infiltration.

The snow that accumulates in the Sawtooths is determined by a few factors as well. Air temperature, frequency of storms, moisture in the air, and even wind. Wind can drift the snow causing the snowpack structure to change and quickly evaporate.

Accumulation will determine the density of the snowpack. The lower layers from the first snowfalls become compressed. Moisture in the snow will affect its density. Even the crystal formation of the snow can affect the structure of the snowpack. Together, density and formation will affect how fast the snowpack melts, and how much water it will produce.

Moisture in the snow is determined by air temperature and how much water is available in the atmosphere. For example, the far western mountain ranges of our country typically receive heavy, wet snow, producing more water. In other areas where the snow is more dry, light, and powdery, it will contain a trace amount of water compared to other regions around the country.

The snowpack in the Sawtooth Mountains will melt with warming ground temperatures, direct sun exposure, and when the temperature from top to bottom reaches 32 degrees. Reaching that constant isothermic state is when the snowpack begins to release, flowing into the ground, and awaiting lakes and streams.

Below Ground

Sawtooth Water Table

The saturated zone is where the pore spaces are filled with water and the very top of this is referred to as the water table. The water table will rise and fall naturally with the change in seasons. Rising to its highest levels in the spring, used up by vegetation throughout the summer, discharging into streams, and lakes resulting in a significant drop. By fall the table may reach its lowest level by as much as 15 feet.

Groundwater exists in two zones. In every space between the rocks and soil beneath the surface of the ground in the zone of saturation. This is where every pore space between rock and soil is saturated with water. It also exists directly above in the unsaturated zone just beneath the land surface mentioned previously. Groundwater can stay underground for thousands of years, or it can surface, filling lakes, streams, wetlands, and other water sources we recreate at and enjoy in the SNRA.

Where infiltration is the capacity of soil to absorb and transmit surface water, recharging is the rate of groundwater replenishment after the effects of infiltration have already taken place.

Recharging of the groundwater occurs by precipitation that occurs after the growing season. There is no recharge during winter as the ground is frozen. Some recharge can occur if midwinter thaws occur. Typically the ground receives the abundance of its recharge from the snowpack melt in the spring, raising the water table once again and beginning the process all over again.